While in Sicily, I was struck by the thoughtfulness and simplicity of ancient Greco-Roman architecture, and I found a set of columns that struck my interest. These Greek columns were built over 2,500 years ago at the end of the Nordic Bronze age and the cusp of the Pre-Roman Iron Age. This timing coincided with the foundation of the first republic in Vaishali Bihar India and the 70th Olympic games.

It was a time of political turmoil and shifting perspectives. The Roman Empire showed its first signs of strength, and wars continued to break out throughout the Mediterranean (as they were apt to do during that time period). One of these wars, the Peloponnesian War, permanently altered the region.

The Peloponnesian War was fought between Athens and Sparta—the two most powerful city-states of that time period—and Carthage was caught in the middle. After three phases of war over the course of roughly 25 years, power shifted from Athens to Sparta. It ultimately ended in Athens’ defeat in 404 BC, and an unofficial peace treaty was signed by the governing powers of Athens and Sparta in 1996 as a symbolic act, as that year marked the 25th century since the war’s end. Around this tumultuous time in history, the Carthaginians sailed their ships west and founded a number of colonies in what is now modern-day Italy. Syracuse in Sicily was one of those colonies.

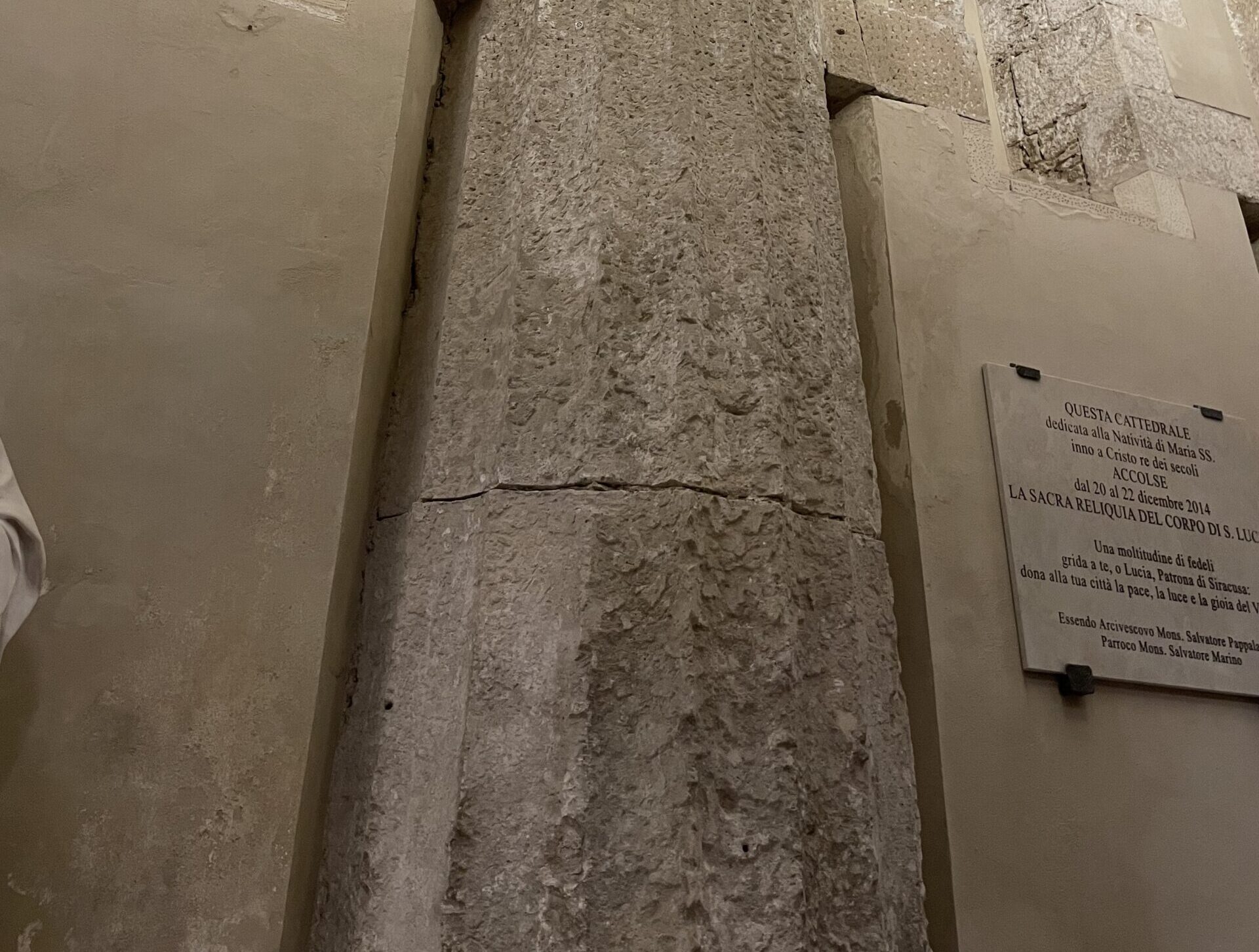

This column—the one that captured my interest—is located in what was the temple of Athena in Syracuse and is roughly the same age as the Peloponnesian war. The column itself is perfect. There is no concrete or mortar holding it together. It is perfectly cut and balanced, signaling excellent craftsmanship. It withstood no less than four major continental earthquakes since it was built. It was originally freestanding, then later integrated into the temple. Once Christianity popped up in an official capacity in the third century A.D., the temple was used for other religious practices and observances, but still remains standing in perfect condition to this day as the cathedral of Syracuse. If these columns are not an example of sustainability, what is?

Architecture has changed so much over the past several thousand years. In recent times, our structures have unfortunately crumbled due to natural disasters and earthquakes. Some of this is inevitable, but it begs the question: what were architects and builders doing thousands of years ago that we cannot seem to accomplish today?

Building a sustainable system is a vital part of building sustainability in the future. While I was in Syracuse, I observed architecture that spans several different periods of history. Surrounded by tumultuous wars and the rise and fall of dozens of empires, they remained unchanged. Yet modern homes only last about 70-100 years before significant repairs are needed to ensure they are livable.

So why am I giving a history lesson—what’s the point?

In centuries past, people (whom current society might consider less technologically advanced) were capable of building things that would withstand the test of time. In modern businesses, and in general, how long do the things we create last? Will our products, structures, and creations last for 2,500 years, or will they fall and be replaced like the empires that grew and fell around this seemingly everlasting column?

We live in a fast culture built on consumerism. We are always focused on the next new product or software update. To us, new indicates advancement, and our focus on fast-changing technologies, styles, and products is allegedly impacting the companies that cater to our fast fashion fascination.

In fact, it is heavily theorized that some companies design their products to break down after a certain period of time in order to ensure that consumers will replace them, bringing in more profit for the company and creating a buy-and-replace purchasing cycle for the customer. This isn’t anything new—in fact, Whirlpool was accused of this same thing as far back as the 1950s. They created a line of washing machines that would last only a few years, forcing customers to purchase new ones. It’s no secret that Apple has been accused of this. In 2017, they admitted to slowing down older iPhones to encourage new purchases. In 2020, they were hit with another lawsuit over supposed “program obsolescence”, meaning they deliberately manipulated the performance of older devices to encourage new product purchases. We know that lifecycle product strategy (shortening a product’s lifecycle to create a demand for more products at a quickened pace) creates more revenue for companies, but it seems that these companies are not motivated by creating a lasting product.

And it isn’t just tech. Apparel purchases rule the eCommerce industry. It continues to grow in sales by 21.8% year over year and reached a total of $110.68 billion in revenue last year despite the pandemic. It also contributes more to environmental damage than almost any other industry due to fast fashion and the buy-wear-trash mindset that dominates consumers’ shopping patterns. The apparel industry contributes to 10% of global carbon emissions and is the third-largest polluting industry in the world, after fuel and agriculture.

We have become, quite literally, the opposite of sustainability in terms of our products, purchasing patterns, and value systems. And the focus on “new” is causing a significant amount of waste and damage to our environment. Why are we building things to break instead of building things to last? Why are we building or altering industries that harm our world instead of helping it?

How would consumer behaviors change if we begin to build well-designed, long-lasting, sustainable products that scale? Essentially, is our obsession with fast and new based on our reactions to businesses creating short-lifecycle products, or did businesses adjust to suit our obsession with “advancement”?

Our current system is flawed, and it’s catching up with us. What does it look like to build not for the sake of expediency, but for the sake of making something that lasts? Whether your company needs to withstand a pandemic or natural disaster, the columns of Syracuse give us a lasting example of how far intentionality and sustainability can go.